Microsoft SQL Server Hacking — TDS Downgrade Attack

Hey there, fellow hackers! As we kick off this new year, it's the perfect time to dive into some research. That’s why we wanted to share an intriguing observation from a deep dive into Microsoft SQL Server hacking via its TDS protocol, conducted by our team member NeCro aka Giannis Christodoulakos. While exploring how SQL Server communicates with clients, he uncovered some weaknesses in the TDS protocol that can be exploited to capture MSSQL account credentials.

Intro

You might be asking, "What on earth is TDS?" And you're definitely not alone! TDS, or Tabular Data Stream, is the protocol Microsoft SQL Server uses to connect with clients, particularly thick-client applications. Through research, it was found that by manipulating the way TDS handles encryption, it’s possible to capture MSSQL account credentials.

In this blog, our team member breaks down how TDS works and examines some of its “features” that can be exploited to retrieve MSSQL account credentials. Our aim is to guide you step by step through this MSSQL Server hacking technique from an ethical perspective, while sharing remediation strategies to secure your assets.

The following article is researched and written by Giannis Christodoulakos.

Motivation

What prompted me to dive into this topic? Well, I kept encountering the TDS protocol during various security assessments, particularly during internal penetration testing. Each time, I couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that there was more to discover beneath the surface. So, I decided to dig a little deeper into the protocol, and what I found was eye-opening.

TDS has some security weaknesses (I’m not calling them vulnerabilities) that often fly under the radar. To put it simply, a classic Man-in-the-Middle hacking attack can easily hijack the connection, downgrade the TDS encryption, and snag MSSQL account credentials. It’s a reminder that even well-established protocols can harbor hidden dangers that we need to be aware of.

TDS Overview

What is TDS Protocol?

Tabular Data Stream (TDS) protocol is a communication protocol developed by Microsoft, primarily used to enable seamless interaction between Microsoft SQL Server and various clients, including applications and other SQL servers. Think of TDS as the middleman that ensures data flows smoothly between a SQL server and a client application, taking care of crucial tasks like authentication, data retrieval and query execution.

TDS Authentication

A vital part of the TDS protocol is TDS authentication. This process acts as the gatekeeper for Microsoft SQL Server, ensuring that clients are verified before any data exchange occurs. It also serves as a facilitator for these data exchanges. To kick off these interactions, the client needs to authenticate with the MSSQL server by entering the credentials for a configured MSSQL account.

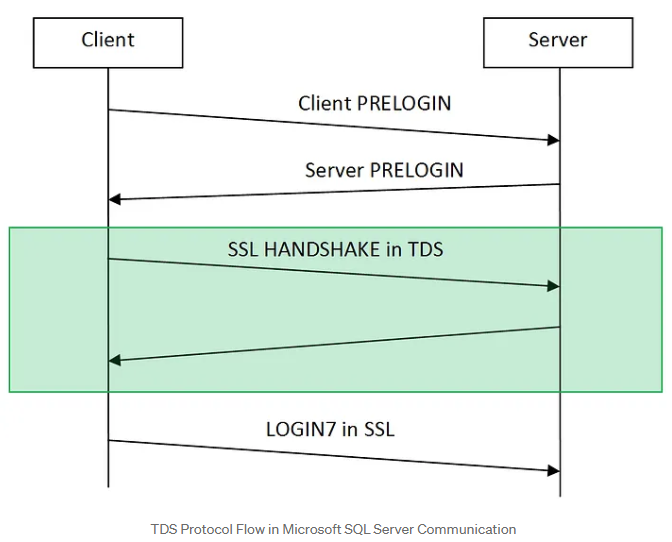

Here’s a quick breakdown of TDS authentication flow:

- PRELOGIN Packet: When a client (like a thick client application) wants to connect to an MSSQL server, it initiates a session with a PRELOGIN packet to establish protocol details like version, encryption preferences and other settings.

- PRELOGIN Response Packet: The server replies with a PRELOGIN packet of its own, responding to the client’s settings and confirming parameters for the session. Key fields in the server’s response include version, encryption preferences, and other compatibility information.

- SSL Handshake (Optional): If encryption is available on both ends, the client and server perform an SSL handshake to establish a secure connection. This step is wrapped within the TDS protocol and uses the settings established during the PRELOGIN exchange to determine encryption.

- Authentication (LOGIN7 Packet): After the initial setup, the client sends a LOGIN7 packet with credentials, including the username and an obfuscated (but easily reversible) password, to authenticate with the server. Whether this packet is encrypted or sent in plain text depends on the encryption preferences agreed upon during the PRELOGIN exchange.

In a nutshell, these steps outline the initial connection flow of TDS authentication.

But wait, there’s more! In the upcoming sections, we’ll dive into ways to manipulate these encryption preferences. Spoiler alert: we might just find a way to trick the client into handing over those cleartext MSSQL account credentials, all while skipping that whole SSL handshake— rude, I know, but who has time for handshakes anyway? Let’s dig in!

How Encryption on TDS Protocol Works

Now, encryption in the TDS protocol is our main enemy to beat if we want those MSSQL account credentials. And, as they say, to defeat your enemy, you’ve got to know its weaknesses. So, let’s dig into how TDS encryption is established.

How to Understand Encryption Settings and Documentation for Hacking

By exploring Microsoft’s protocol documentation, we gain insight into how the client and server determine encryption settings.

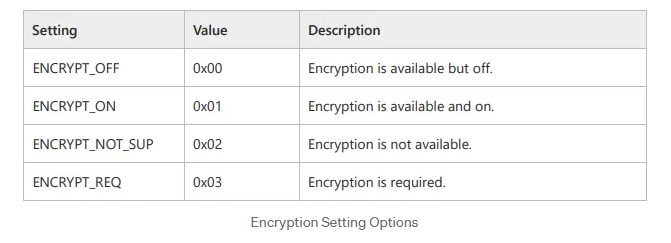

When a client initiates a connection to an MSSQL server, both parties must agree on whether to use encryption. This agreement occurs during the PRELOGIN handshake, specifically in the Client and Server Prelogin Response Packet. During this phase, both the client and server share their preferred encryption settings by selecting one of the following four options:

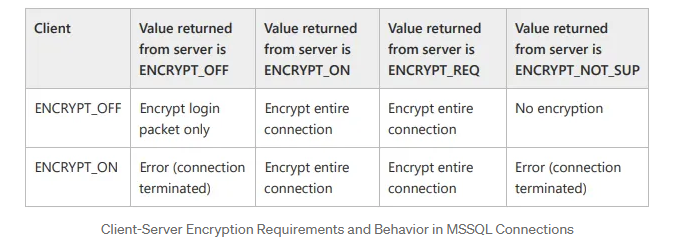

With these options in mind, the client and server exchange their encryption settings through PRELOGIN packets. Based on these options, they decide how to proceed regarding encryption. Assuming the client supports encryption (which is almost always the case), the server expects the client to follow these rules:

As a result, based on the encryption settings outlined in the table above, both ends will determine the appropriate encryption preference for the connection.

It’s important to note that the default encryption settings for both the client application and the MSSQL server is ENCRYPT_OFF. By default, since both sides support encryption, they will establish an encrypted connection to securely exchange the Login packet data (Based on the table above).

TDS Authentication Flow

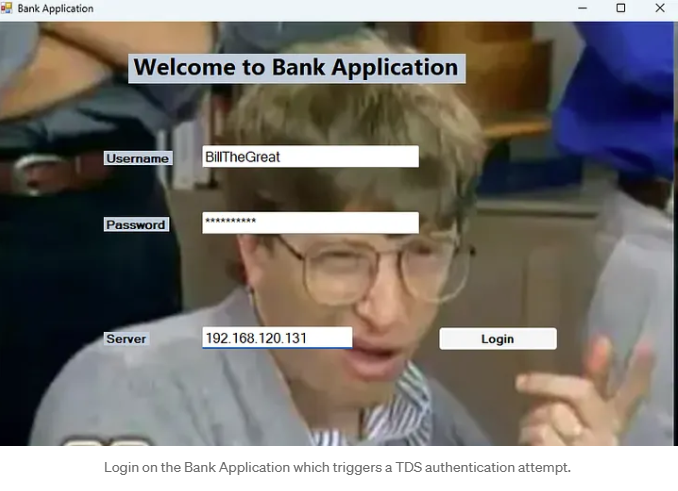

Now, let’s break down this process with a practical example. I’ve put together a dummy thick client application to vividly illustrate the connection flow in its default state:

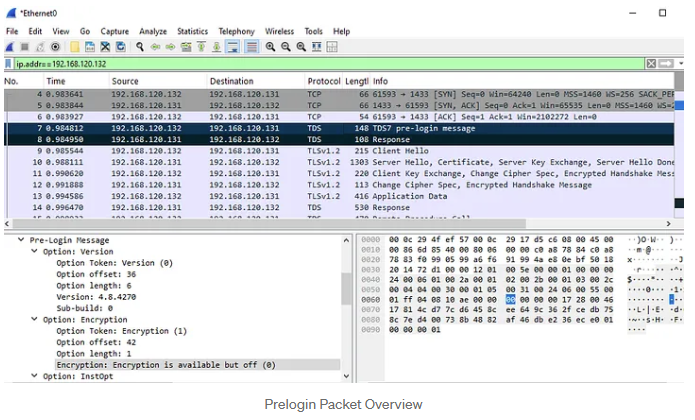

1.When a client connects to the MSSQL server, it sends a TDS7 pre-login message with the default encryption setting, ENCRYPT_OFF (0x00).

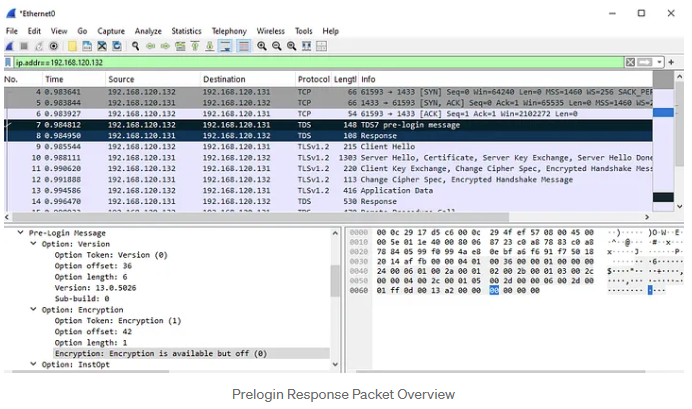

2.In the server's Prelogin Response Packet, which has a similar structure to the client's packet, we also see the default encryption preference.

According to the encryption settings outlined in the table above, we expect the application to create an encrypted connection during the Login Packet. This expectation is validated by the subsequent packets (9–12), which demonstrate the establishment of an SSL session using TLSv1.2. The Login Packet is represented as packet 13 in the screenshots and contains the encrypted application data.

The Challenge and the Solution

Our primary challenge on our way to the MSSQL server hacking is determining how to bypass encryption to capture the Login packet containing the credentials we are seeking. As noted earlier, the application and server communicate their encryption preferences through the PRELOGIN packet. Based on this exchange, we can identify four potential scenarios that could allow us to downgrade the encryption on the Login packet and successfully capture the credentials.

Scenario 1 (Default State)

Client: ENCRYPT_OFF

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_OFF

This is the most common scenario where both the client and server are in their default configurations. In this state, while encryption is supported, it is not required. Typically, both parties will agree to encrypt the login packet. However, in the event of a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack, we can intercept the server's PRELOGIN response and modify its encryption setting to ENCRYPT_NOT_SUP, which forces the connection to proceed without encryption.

When the client receives this altered PRELOGIN response, it checks the encryption setting. Seeing that encryption is reported as "not supported" (based on the modified value) and being configured with ENCRYPT_OFF, the client sends the login packet without encryption. This lack of encryption allows us to capture the login packet in plaintext.

It's important to note that the server initially recognizes the client's ENCRYPT_OFF setting and responds accordingly (with ENCRYPT_OFF). However, due to our MITM modification, the client believes that encryption is not supported (ENCRYPT_NOT_SUP). Nevertheless, the server still expects encrypted communication. As a result, when the client sends its credentials in clear text, the server will terminate the connection because it is waiting for encrypted data. Consequently, further communication cannot take place, and no additional packets can be captured through the MITM attack. Therefore, to sustain the attack or manipulate the connection further during this hacking process, we would need to modify the client’s PRELOGIN packet to align with the altered encryption setting (ENCRYPT_NOT_SUP).

Scenario 2

Client: ENCRYPT_ON

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_OFF

In this hacking use case, the client enforces encryption, meaning the connection is encrypted by default. If an attempt is made to downgrade encryption, the client will terminate the connection. To bypass this restriction, we would need to modify the client application’s configuration (connection string), changing its encryption setting to ENCRYPT_OFF. Once this change is made, we can proceed with the downgrade attack as described in Scenario 1.

Scenario 3

Client: ENCRYPT_OFF

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_ON

In our third hacking scenario, the server enforces encryption, meaning the connection will be encrypted unless tampered with. We can try hacking it with a MITM attack and modify the server's response to set encryption to ENCRYPT_OFF (similar to Scenario 1), which would force the client to send credentials in plaintext. However, there is a limitation: because the server enforces encryption, if we attempt to forward an unencrypted connection to the server, the client will disconnect, as the server will not accept it. Nevertheless, this still allows us to capture the credentials from the login attempt, as we can trick the client into believing that the server does not support encryption.

Scenario 4

Client: ENCRYPT_ON

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_ON

In this case, both the client and server enforce encryption, which may initially seem to make downgrading impossible. However, if we have access to modify the client configuration (as in Scenario 2), we can change the client’s setting to ENCRYPT_OFF and subsequently proceed with the downgrade using the approach from Scenario 3. This allows us to force a plaintext connection even when both ends initially enforce encryption.

Conclusion

In our exploration, we’ve delved into four intriguing scenarios for downgrading the TDS protocol's encryption, each offering a creative ethical hacking solution to sidestep its encryption requirements. The main hurdle we face? If the client adamantly enforces encryption, our success hinges on our ability to tweak either the client’s encryption settings or the source code.

Putting It All Together: A Hacking Review

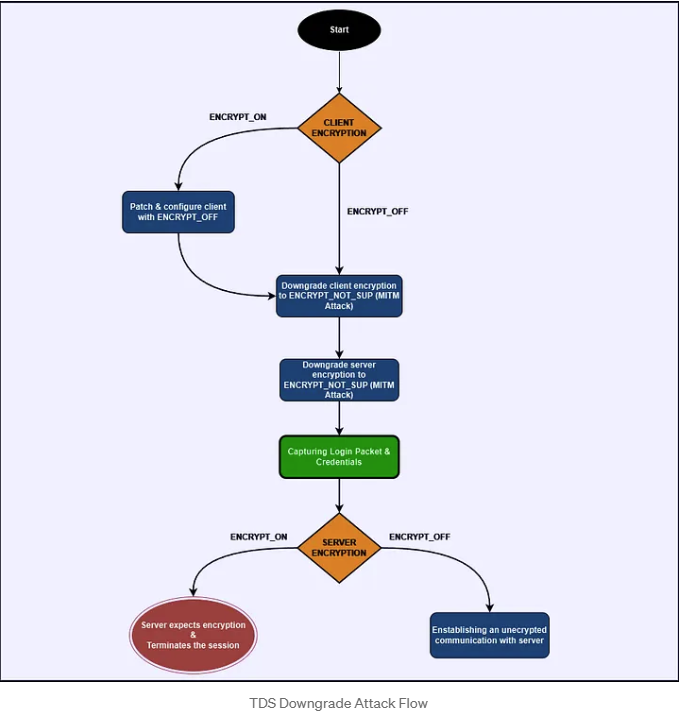

In summary, by demystifying how TDS encryption operates and skillfully utilizing the PRELOGIN handshake, we can manipulate the encryption preferences to gain access to valuable MSSQL credentials. Here’s how the process unfolds:

- Identify Encryption Settings: Start by checking the client’s encryption settings as outlined in the Prelogin packet.

- Alter Client Encryption Setting (Optional): If the situation calls for it, modify the application's encryption setting. This allows you to send the Login packet unencrypted, even if the client has set it to ENCRYPT_ON.

- Man-in-the-Middle Attack: Set the stage for a MITM attack between the client and the MSSQL server. Intercept the PRELOGIN packet and take the opportunity to adjust the server’s encryption response to ENCRYPT_NOT_SUP.

- Capture the Credentials: With encryption now disabled, the LOGIN7 packet—containing those all-important credentials—will be transmitted in plaintext. Capture this packet to retrieve the MSSQL credentials.

- Establishing Unencrypted Communication: If the server isn’t enforcing strict encryption policies (i.e., it does not require the ENCRYPT_ON option), an unencrypted connection can be established between the client and the server. This opens the door to passive sniffing of unencrypted data flowing between them without further interference.

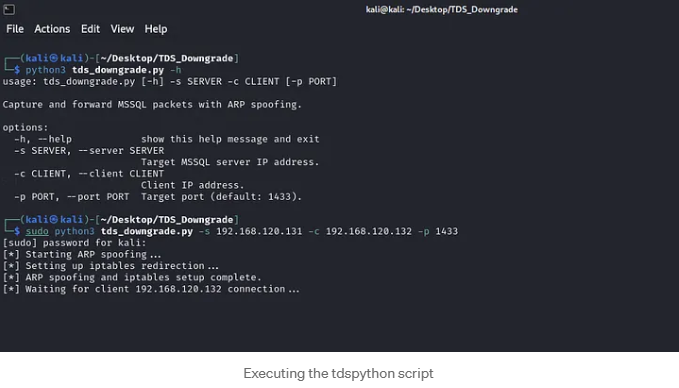

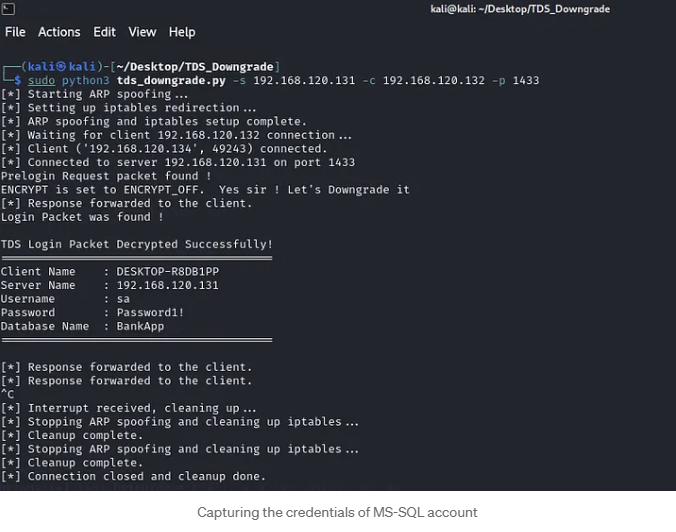

Practical Attack: A Hands-On Hacking Approach

In this section, we'll walk you through how to address the scenarios we've discussed effectively. For this case, we've got a demo thick-client application at our disposal, along with a tailored Python exploit NeCro crafted to execute a downgrade on the TDS. This hacking script orchestrates a Man-in-the-Middle attack, exploiting the server’s Prelogin encryption options to compel an unencrypted connection. If you're curious to see the actual code in action, you can check it out in my GitHub repository here:

Client IP: 192.168.120.132

Kali Machine IP: 192.168.120.129

MSSQL Server IP: 192.168.120.131

Scenario 1

Client: ENCRYPT_OFF

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_OFF

In this hacking use case, we simulate a thick-client application that communicates with an MSSQL server. By inspecting the traffic through Wireshark, as we did in previous sections, we confirm that neither the client nor the server enforces encryption, as it is set to the default value ENCRYPT_OFF. To exploit this weakness, we use the Python script `tds_downgrade.py`.

Execute the script with sudo privileges, as elevated permissions are required for the iptables and arpspoof tools to redirect our traffic during the man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack.

While running the script, we wait to capture a connection to the MSSQL server. We then trigger a connection from the thick client application running on the client host, and voilà! We successfully captured the credentials for the MSSQL account, which belongs to the system administrator.

Scenario 2

Imagine you're trying to connect to an application that enforces encryption right from the start, specifically during the initial connection (the PRELOGIN packet). In this case, any attempt at a downgrade attack will hit a brick wall because the application simply won't allow connections that can't establish secure encryption. But don’t bother. There’s an exciting hacking workaround!

Before we roll up our sleeves, let’s pinpoint when an application mandates encryption versus when it doesn’t. It all boils down to the connection string! This string is crucial as it outlines the parameters we use to connect to the database. Here’s a quick peek into the structure of a connection string:

Server=myServerAddress;Database=myDataBase;User Id=myUsername;Password=myPassword;Forcing an Encrypted Connection

To ensure your connection is secure, the connection string must include the Encrypt parameter set to True. This tells SQL Server to activate SSL/TLS, ensuring that all data transmission between the client and the database is encrypted.

Server=myServerAddress;Database=myDataBase;User Id=myUsername;Password=myPassword;Encrypt=True;Leaving Encryption as Optional

To make encryption optional, you can either set Encrypt=False in the connection string or omit the Encrypt parameter altogether:

Server=myServerAddress;Database=myDataBase;User Id=myUsername;Password=myPassword;

Where to Find the Connection String

When you're on the hunt for that connection string, you’ll typically uncover it in one of two handy spots:

- Hardcoded in the application’s source code

- Stored in one of the application’s configuration files

If the connection string is found in a configuration file, you can easily edit it to remove or adjust the `Encrypt` parameter. However, if the connection string is embedded in the source code, you will need to use a decompilation tool to extract the code, find the connection string, and modify the encryption settings.

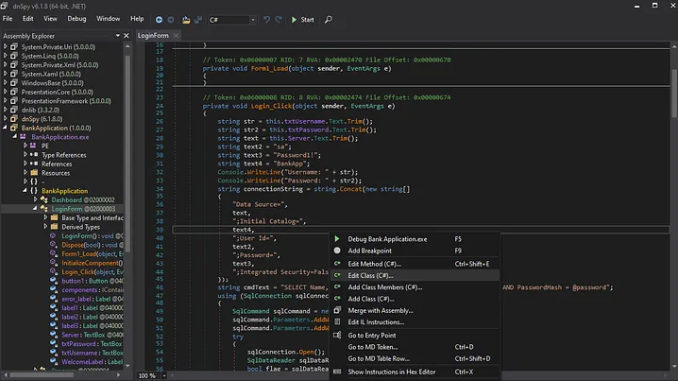

Patching Connection String with dnSpy

For this specific case, we will be using dnSpy. This tool is a popular open-source .NET debugger and assembly editor that allows users to decompile, edit, and debug .NET applications. You can find dnSpy available for download here:

Step 1: Open the Application in dnSpy

- Launch dnSpy.

- Go to File > Open and select the .exe or .dll file of the application you want to decompile. In our case, we select the BankApplication.exe.

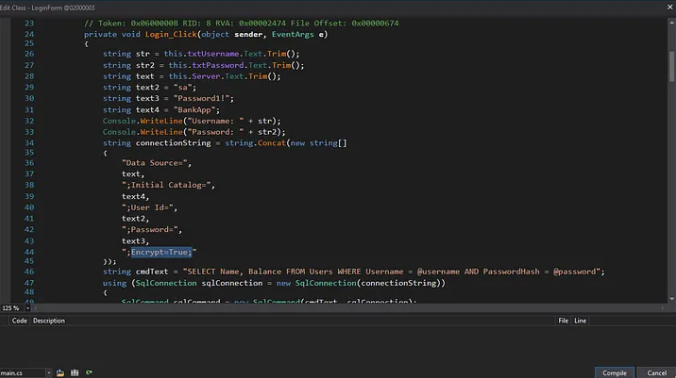

Step 2: Locate the Connection String and Edit the Class

- Right-click on the method containing the connection string and select Edit Class(C#). This opens the class in dnSpy’s built-in editor.

Step 3: Edit the Connection String to Modify Encryption

- Find the Encrypt=True portion within the connection string and change it to Encrypt=False to make encryption optional

Step 4: Compile and Save Changes

- After editing, click Compile in the editor window to apply the changes. To save the modified assembly go to File > Save Module.

- Choose to Save the modified assembly. This will overwrite the original file by default, or you can specify a new path to keep the original.

Now that the application has been patched to use the ENCRYPT_OFF setting, you can proceed as outlined in Scenario 1 to capture the credentials.

Scenario 3–4

Client: ENCRYPT_OFF | ENCRYPT_ON

MSSQL Server: ENCRYPT_ON

In scenarios where the server enforces encryption, downgrading the client's encryption settings will not suffice, as the server will reject any unencrypted connection. This means that while we may intercept and capture the initial login credentials, we will be unable to maintain a continuous connection to the actual MSSQL server to capture further queries, sensitive data, or any ongoing traffic.

Therefore, our primary focus is only on capturing the credentials. To achieve this, we need to replicate what we did in Scenario 1. However, if the client application is enforcing encryption, we’ll first need to modify the encryption settings as we did in Scenario 2 by patching the connection string to set it to ENCRYPT_OFF. Once that’s done, we’re ready to execute the hacking attack as we did.

With everything set up, trigger a connection attempt from the client application to the MSSQL server, and capture the plaintext credentials!

A Few Quick Tips

For demonstration purposes, we used an input field in the thick-client application to select the MSSQL server. In real-world penetration tests, this option may not always be available. If it is, you can skip the entire MITM setup. Just swap the MSSQL server’s IP address with that of the attacking host while running Responder to capture those valuable credentials.

If you encounter a client enforcing encryption, remember: patch that connection string to turn off encryption before you proceed to snatch the credentials.

Post-Attack Strategy

Once you’ve captured the MSSQL account credentials, it’s time to assess the privileges tied to that account. Connect to the database using those credentials to check if you’ve got admin rights or some high-level privileges. If it does, verify whether xp_cmdshell, a stored procedure that allows executing shell commands directly from SQL Server is enabled. If it’s disabled—don’t worry, you can work to enable it. Once xp_cmdshell is active, you can leverage it to execute commands on the underlying host, potentially gaining remote code execution and expanding your access within the target environment.

Recommended Remediation: Strengthening MSSQL Security

To keep MSSQL credentials secure and prevent potential attacks, consider implementing the following strategies:

Use Integrated (Windows) Authentication: Switch to Windows Authentication instead of SQL Server’s native authentication, which reduces the need to transmit SQL credentials over the network. Integrated Authentication relies on Windows credentials, adding a layer of security against credential interception.

If enforcing this option isn’t feasible, it’s crucial to implement all the following rules carefully to mitigate the impact of the issue:

- Set Both Client and Server to Enforce Full Encryption (ENCRYPT_ON)

- Ensure that both the MSSQL server and all client applications are configured with ENCRYPT_ON. This prevents any downgrading of encryption, securing the session from the initial connection through data exchange.

- Restrict Access to Connection Configuration

- Prevent unauthorized modifications to connection configuration settings. Limit permissions on configuration files or embedded connection strings within the application to reduce the risk of encryption settings being altered to ENCRYPT_OFF.

- For compiled applications, obfuscate or encrypt connection strings within the source code to make tampering with settings more difficult.

- Validate SSL Certificates on Both Ends

- Enforce strict SSL certificate validation on both the client and server during the SSL handshake to prevent unauthorized systems from impersonating the MSSQL server.

- Ensure that the SSL certificates used by the MSSQL server are signed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA) and not self-signed, as this reduces the likelihood of MITM attacks with forged certificates.

Affected Versions

Be aware that the TDS downgrade attack predominantly targets versions of the Tabular Data Stream (TDS) protocol prior to TDS 8.0. These older versions, utilized by Microsoft SQL Server, allow optional encryption and don’t strictly enforce secure communication during the PRELOGIN handshake. Fortunately, Microsoft introduced TDS 8.0 in certain MSSQL versions, bringing enhanced encryption and security measures against hacking attempts. As a result, servers using TDS 8.0 or higher are resistant to these downgrade attacks.

TL;DR

Microsoft SQL Server’s TDS protocol allows optional encryption during the PRELOGIN handshake. By abusing this design through a Man-in-the-Middle attack, an attacker can downgrade or disable encryption and force the client to send the LOGIN7 packet in plaintext. This enables the capture of MSSQL credentials, even in environments that appear to support encryption. The attack is especially effective against legacy TDS versions and misconfigured clients that do not strictly enforce ENCRYPT_ON.

Conclusion: A Hacking Apocalypse

This research highlights a critical, often overlooked reality: supporting encryption is not the same as enforcing encryption. This TDS protocol’s flexibility, which is originally designed for compatibility, creates a fertile ground for downgrade attacks when encryption policies are misconfigured or loosely enforced.

By carefully manipulating the PRELOGIN handshake, an attacker positioned as a Man-in-the-Middle can force client applications into transmitting MSSQL credentials in plaintext. The attack does not rely on zero-day vulnerabilities or exotic exploitation techniques, but instead abuses expected protocol behavior, default settings and real-world operational shortcuts. This makes it both stealthy and highly practical during internal penetration tests and assumed-breach scenarios.

From an offensive perspective, the TDS downgrade hacking attack is a powerful reminder that credential exposure can occur before authentication even completes. Even when a database enforces encryption, credentials can still be harvested if the client is tricked into believing encryption is unavailable. In environments with hardcoded or poorly protected connection strings, this hacking risk increases significantly.

From a defensive standpoint, the takeaway is clear:

- Optional encryption is a liability.

- Client-side configuration matters just as much as server-side policy.

- Legacy protocol versions silently undermine modern security expectations.

Organizations relying on SQL Server must treat database connectivity as part of their threat model, not just the database itself. Therefore:

- Enforcing ENCRYPT_ON everywhere

- Validating certificates

- Protecting connection strings

- Moving towards Integrated Authentication

are no longer “best practices”; they are baseline requirements.

Ultimately, the TDS Downgrade Attack serves as a case study in how design trade-offs made years ago can still shape today’s attack surface. For attackers, it expands the credential-harvesting playbook. For defenders, it’s a sharp reminder that security controls must be explicit, enforced, validated, and never assumed.